The capsizing of 'Torm Alexandra' in Monrovia 2001

By Michael B. Clausen, (formerly Line Control in Torm Lines)

Torm's line department started in 1985 as the first shipping company a feeder service on the West African coast. Initially, it was a minor supplement to the primary activity from the US Gulf and east coast to West Africa, primarily to serve the smaller Nigerian river ports.

Feeder service starts with Torm Africa

It started with 'Torm Africa', which was bought in 1985, at the initiative of the then line manager, captain Henrik Schrum. It had no crane of its own, but before long, a decommissioned crane from ØK, which had been on 'M/S Meonia', was purchased. 'Torm Africa' loaded from the large ships in Abidjan.

To better serve our customers in the USA at all ports, a service from Abidjan to Monrovia, Freetown, Conakry, Banjul, and Dakar was started later. The first ship in this service was a German charter ship 'Point Lisas' with a size of 3050 DWT, which made nearly 50 trips.

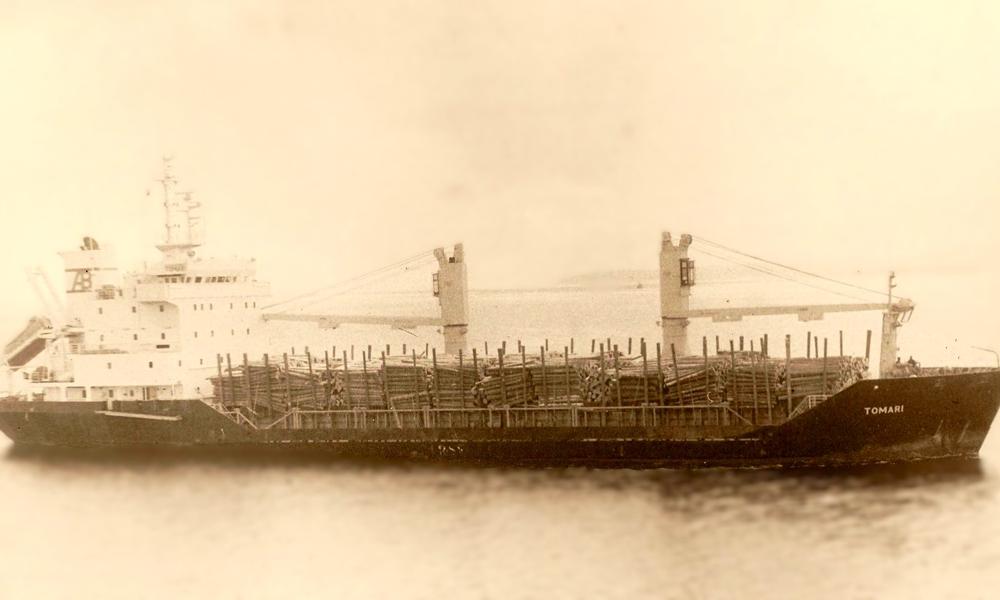

Later, ships of the Uglegorsk type with a size of 4700 DWT / 221 TEUs were used. The cargo intake became so good - also with local cargoes - that a further ship of the same size was chartered. This provided a departure every 12th day.

In the meantime, Henrik Schrum had retired and his successor, Peter Albeck, did great work to further grow Torm Lines.

In the transatlantic trade, we ended up with a departure almost every week with ships up to 24,000 DWT, among others with the purchase of 'Torm Freya', which was the former 'Ove Skou'.

Thus, Torm became the market leader on the USA-West Africa route, and on the southern loop, an upgrade was also made with a service all the way down to Matadi in connection with the acquisition of a smaller competitor, US Africa Navigation. Abidjan was the transshipment port. We then operated four feeder ships in the size of 5000 DWT.

Since we were pleased with the Uglegorsk type for the northern loop, two such ships were chartered from the shipping company Hansen and Lange. One was renamed 'Torm Alexandra'. As far as possible, our regular charter ships were given a Torm name.

In Abidjan, we had employed Captain Mark Plutte as supercargo in Abidjan, where at times we had both two large ships and two feeders. So, it was important to have skilled people ensuring adherence to the schedule and to make the most of the ships' capacity. Mark Plutte had previously been the captain on Torm Africa.

Torm Alexandra was loaded and set sail for its demise in Monrovia

Mark Plutte was not in Abidjan when 'Torm Alexandra' was loaded for what turned out to be her final voyage in early 2001. 'Torm Alexandra' was loaded by our stevedore in Abidjan, SIVOM, solely with the help of the ship's captain and chief officer. However, Mark Plutte was back before the departure and noted that 'Torm Alexandra' left for Monrovia fully loaded.

In Monrovia, private agencies also had their own stevedore companies, but this was suddenly stopped – from the highest level – just before 'Torm Alexandra's' call. Therefore, the ship was handed over to a new stevedore company in which the transport minister allegedly had interests. They were entirely inexperienced in handling containers. Our agent UMARCO couldn’t do much about it.

The Uglegorsk type had a low freeboard, particularly when fully loaded. The captain instructed the stevedore to start with the containers on the land side and only one container at a time, considering the ship's stability. This recommendation was not followed by the new stevedore, who instead began to unload 2x40’ containers with a spreader simultaneously from the water side.

When such a lift landed, the ship listed significantly towards the quay. The crane operator got scared and did not lower the crane when the containers landed. Due to the considerable list, the freeboard went underwater. The stevedore on land was also too slow to open the twist-locks that held the containers in place, and when they finally did get them open, the ship swung very strongly to the sea side.

With this first swing, even more water came onto the deck due to the low freeboard. It was made worse by a hatch providing access from the engine room to the deck that had been left open, so when Torm Alexandra swung several times strongly back and forth, more and more water got into the engine room. This caused a permanent list and eventually led to the ship laying itself completely over against the quay - and remained lying. The list caused several containers to break their lashings and fall down onto the quay.

The crew was, of course, evacuated from the ship, and it wasn't long before looting of both the ship and the containers, which lay scattered in disarray, began – despite the police being called to stand guard.

The sad aftermath

The shipping company's insurance company, SKULD, began negotiations with the two Dutch salvage companies, Jan de Nul and Boskalis, about the salvage of the ship. Technically, it was probably a manageable task, but it quickly became apparent that the authorities in Liberia wanted to exploit the situation and demanded money to allow it. So the ship remained – first at the quay and later towed out, where it blocked part of the harbor for several years.

There was a human tragedy as a result of the authorities' greed in preventing the salvage, with locals – often young people – swimming out to enter some of the containers still on board. Some drowned in the attempt to gain an income, which would have made them somewhat wealthier than "honest work" in Monrovia could.

DR made a documentary about the case in "Horizon" years ago. Liberia had recently been through a long and bloody civil war – or more a warlords' struggle for power and their militias' terrorization of the general population – and although it had stopped in 2001, it was still a quite lawless state.

Torm West Africa Line’s swan song

Torm Alexandra, however, gave us employees an extra year at our – for many of us – long-term workplace. Among us was Peter Albeck, who had been there since the inception of Torm's continuation in 1980 of Dafra Lines' GULWA and BALWA lines, after this shipping company's bankruptcy in 1979. I myself started in 1981. There were already “rumors” that Torm’s new management – after the Greek Gabriel Panayotides’ “run” on the stock in 2000 and his subsequent control of the company – was planning to divest the liner activity.

That Maersk Line was a likely buyer was an open secret. However, at Esplanaden, it was later revealed that the unresolved situation in Monrovia was seen as potentially harmful to the company's activities there and in the larger area. Still, Torm Lines continued its aforementioned activities without any consequences, including in Monrovia.

But time heals all wounds, and in 2002 the sale became a reality. On September 11, Torm’s board along with two from Maersk Line’s leadership entered the liner department and announced that from that point, Maersk would take over the operations, and employee contracts would be transferred.

There would be a three-month “business as usual” period, after which the container activities would be fully integrated into Maersk Line’s service via Algeciras, and the piece goods segment including oil drilling equipment and other items from the U.S. Gulf would be handled by the subsidiary Safmarine. However, this was to a much lesser extent. Thus, September 11, 2002, also became a fateful day for the employees of Torm Lines – though not to be directly compared with the tragic day in New York a year earlier.

Already in October, most were moved to Esplanaden and Maersk West Africa's premises in Christianshavn as well as some to Safmarine in Antwerp. However, most were only there for a short period, and I myself started anew at CEC in February 2003.

Three years after the accident, the ship's insurance company found an amicable solution with the Liberian authorities. The ship was raised, towed out of the harbor, and then sunk in deep water far from the entrance to Monrovia.